A growing number of planners are facing a happy dilemma when it comes to selecting a gaming resort: Native American resort or commercial resort? Increasingly, tribal properties are getting the nod.

In some cases, Native American resorts are the only casino operations available. Other planners see potential savings from more flexible rates, lower taxes and rising service levels. And some planners see a strong plus in tribal cultural connections that turn a Native American resort meeting into an event like no other.

“We hosted the U.S. finals for the women’s Olympic boxing team last year,” remembers Mimi Hall-Gustafson, director of sales for Northern Quest Resort & Casino, a four-star, four-diamond resort owned by the Kalispel Tribe of Indians near Spokane, Wash. “We did a traditional blanket ceremony for the winners in each of the three categories. It was an event that no one, not even the competitors who did not go on to the Olympic Games, will ever forget.”

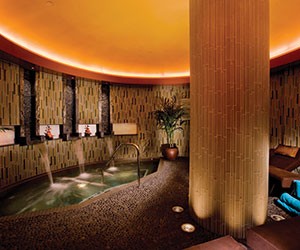

Tribal art and culture are important elements at the 250-room property. Northern Quest has 22,000 square feet of group space, including the largest ballroom in Eastern Washington at more than 11,000 square feet. Tribal motifs are everywhere, from the river pattern woven into throw blankets designed exclusively for the hotel to river rocks and indigenous treatments at Le Rive, Northern Quest’s luxury spa.

Different Tribes, Different Looks

Not all Native American resorts have a casino on property. But most have one nearby. In New Mexico, the Pueblo of Pojoaque built the Buffalo Thunder Resort & Casino, then expanded with the nongaming Hilton Santa Fe Golf Resort & Spa at Buffalo Thunder. Christine Windle, a Hilton director of sales and marketing, pitches the properties jointly.

“There is a lot of money being made on the casino floor,” she explained. “That gives financial support to the resort of the resort. It provides a huge advantage for planners. Most resorts focus on rate and would rather have rooms go empty than cut rate. I would rather have my rooms occupied than empty, period.” PageBreak

Not all tribally owned resorts see their cultural heritage as a marketing vehicle. Some tribes would rather not sell culture. And some markets would rather not buy culture.

In Pendleton, Ore., the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservations Casino focuses more on casino and group amenities at its Wildhorse Resort and Casino than on tribal culture and traditions. The largely regional drive market is more interested in Wildhorse’s 301 rooms, 14,000 square feet of meeting space, casino and entertainment options than in cultural amenities.

“We generally only do cultural-type things for Tribal events, as they are the only ones that request anything of the sort,” explained resort spokeswoman Tiah DeGrofft.

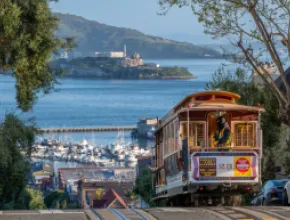

The Tulalip Tribes has taken its marketing programs in the opposite direction. The tribe’s Native American heritage is a key marketing and sales message as well as the dominant visual motif at the Tulalip Resort Casino just north of Seattle. The entrance is flanked by imposing 25-foot tall carved house posts, sculpted metal salmon hang from the ceilings, and traditional masks are a recurring design element.

“Art is key for the resort,” says Kenneth Kettler, resort president and chief operating officer. “It represents our cultural history and traditions. It reflects the more-modern side of our traditional outlook.”

If tribal art is a given for meetings, tribal ceremonies are not. Some Native American resorts routinely offer tribal blessings and other ceremonies. Other resorts focus on artistic and cultural elements.

“Many ceremonies that might be considered entertaining are just that—ceremonies,” Kettler says. “Commercializing the sacred is not welcomed by many.”

Water and fish are recurring visual elements throughout Tulalip’s 370 rooms and 30,000 square feet of meeting space. The artistic elements are taken directly from tribal tradition. Planners who want to delve deeper into tribal culture can use the nearby Hibulb Cultural Center with its 23,000 square feet of interior space and 50 acres of nature preserve. PageBreak

Tribes and Brands

In New Mexico, the Hyatt Regency Tamaya Resort & Spa uses tribal ownership as a key sales advantage.

“Being tribally owned gives you a unique destination and program,” says Troy Wood, director of sales. “We can give your attendees an experience they have never had before. The whole tranquility of the Pueblo culture comes through in every one of our events.”

The resort is located on more than 500 acres owned by the Pueblo of Santa Ana, halfway between Albuquerque and Santa Fe. Tribal competitors in both cities are vying for the same corporate and association events as his 350 pueblo-style rooms, 21,000 square feet of indoor function space, 50,000 square feet of outdoor space and a 16,000-square-foot tribal-themed spa.

Wood is selling one of the only international-brand resorts in all of New Mexico. He is also selling one of the largest tribal resorts in the entire nation. And for planners who want to incorporate a social responsibility element, Tamaya has a unique program that lets attendees help rehabilitate abandoned horses.

“Planners know that profits from the resort go back to the Pueblo people, not to a bank or a real estate investment trust,” he explains. “Knowing that you are benefiting real people adds a unique twist to the event.”

The Pueblo emphasizes the tribal connection. Every attendee gets a traditional coral necklace as a greeting. Tribal dancers are almost a given for every group. There are traditional ovens around the pool and traditional Southwest ingredients are part of every menu. Planners seem to appreciate the difference.

“When you are sourcing a program, you learn pretty quickly that everybody has already done Florida and Vegas and Hawaii,” Wood says. “This is a hidden gem. Planners can give clients a new venue and a completely new feeling here.”

In Phoenix-Scottsdale, the Gila River Indian Community has created a similar brand-name strategy. Without tribal ownership, the 500-room resort with 180,000 square feet of event space, championship golf and a spa wouldn’t even exist, says spokeswoman Stephanie Sanstead.

“The reason we opened was to showcase the Pima and Maricopa cultures,” she explains. “When the community decided to build a resort, they called all the big dogs to the table—Starwood, Hyatt, Fairmont, Hilton—and told them ‘we want to feature Native American culture.’ Starwood offered to break the rules to make it happen. We bent, broke and abandoned more than 100 Sheraton rules to create and open this property. This resort is about sharing culture, sharing with visitors a sense of our place in the universe.”

Fred Gebhart is a frequent contributor to Meetings Focus and a veteran travel writer.